Toasts and Chars

After the initial release of the Wood Primer, my work on it fell behind and stopped altogether while I focused on articles for other sites and took over some of the moderation responsibilities over at /r/homebrewing, notably, the Reddit Homebrewing Competition. I’ve also been working on something called “The Brewery”, something I’ll post about later.

Really, I think the most valuable part of this blog is the wood primer and the exploration of brewing with wood, which is the reason this blog started. Here we are hosting move and a year later, and it’s time to refocus and get back to why we are really here.

Every now and then, I’ll get an email or message about a specific wood question, and one of the ones that comes up pretty often is “What is the difference between toast and char?”, something that wasn’t even mentioned in the original primer. I took some time to really research this one, and to test it out myself utilizing some awesome resources, quite a few provided by /u/chino_brews.

So, what are they?

Toasting and charring are two ways that barrels are treated prior to being used. Basically, toasting creates the “red layer” but doesn’t necessarily change the surface of the wood in a drastically noticeable way aside from color. These toasts change the chemicals in the wood, giving the barrel certain characteristics that can be imparted to the barrel’s contents. Charring can also create a red layer, but more importantly it creates a much heavier layer on the outside of the wood because the wood catches fire. So both of these steps change the composition of the wood, and changes the characteristics the barrel can impart, but the key difference is that toasting rarely involves the flame contacting the wood for any extended period of time, while charring involves the wood catching fire.

Toasting

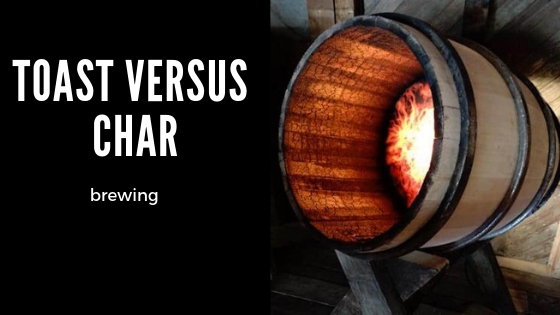

Barrel being toasted.

Toasting typically occurs before the charring process, and takes places over a longer time with a smaller flame. As seen in the image on the right, the barrel is placed over (but not in contact with) a flame so that the inside of the barrel is heated. This heat “toasts” the wood, and breaks down chemicals, namely lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose. The breakdown of these chemicals causes different flavors and aromas to develop, which can then be extracted into the barrels contents. You can read more about toasting and the chemical changes in The Big Wood Toasting Post.

Charring

Barrel being charred.

Charring is a short (the intense “alligator char”, or char #4, only takes about 55 seconds), high-heat process that creates a level of char (Char #1 through Char #4) which “chars” the wood and causes it to crack. The purpose behind charring is two-fold: The first is that the char creates a sort of natural carbon filter which absorbs sulfur compounds, and the second is that the cracking caused by the char allows the barrel’s contents to penetrate the wood. Charring also tends to develop a small layer of toasted wood, called the “red layer”. Barrels may or may not be toasted before this step as well.

The levels of toasting and char vary greatly depending on the vintner/distiller and the barrel’s contents. For example, in the U.S., bourbon must be stored in charred oak containers, while corn whisky does need to be in a barrel (new or used), but not necessarily in a charred barrel.

If you read the Big Wood Toasting Post, you’ll remember that the heat in the toasting process causes cellulose, hemicellulose, lignins, and other compounds to break down and create different flavors/aromas from the barrel. Charring works the same way.

Char levels.

The four traditional char levels are Char #1, #2, #3, and #4 which is also referred to as “Alligator Char”. The lighter chars tend to be “spicier”, with more of those sweet and oak characters we get from a low-medium toast. Darker chars tend to be a bit more toasty and will have more prominent vanilla characteristics.

Charring at home

I’m all about DIY solutions, especially when it comes to brewing. Getting down a solid toasting process is something I’ve spent quite a bit of time working on, and I’d never really addressed using char in homebrew.

One of my favorite beers (by one of my favorite breweries) is Serpent Stout by The Lost Abbey. It’s thick, full of bitter chocolate and bold roast flavors. All around a great beer. When I first had it, there was a quality I couldn’t quite place, some what acrid and sharp, but still pretty wonderful. The flavor seemed at home in a stout.

I did some research, in their QR code (RIP random kitten) they mention that a portion of the beer (10%, according to this recipe from their lead brewer [supposedly] and this information from their microbiologist) is fermented in freshly emptied bourbon barrels which, as we know from earlier, are required by law to have a char (typically a #3). According to those sources, the char is where those flavors come from.

And of course I had to try it out.

Around the time I was planning the beer to test this I was contacted by Rex of The Brew Bag to see if I’d like to review the Brew Bag. Rex is a sponsor for RHC (and is giving away some custom Brew Bags!), and I’d read a lot about the Brew Bag from other reviews. I was eager to try it for myself, so I agreed. You can read more about my review and experience with The Brew Bag here. No affiliate links or anything, just love for a great product!

Charring is pretty simple. Get some wood and the appropriate toast, with the idea that the layer on top will be a bit darker than the toast throughout. This is a good thing, because the char will open up the wood a bit and the layers of toast will provide more complexity.

Get a torch, light ’em up. The short, high-intensity flame is what you’re looking for, you can use the chart above as a guide to the char levels. The wood will catch fire, don’t worry about it, keep the pressure on.

Once you think you have the cubes where you want them (feel free to char one side, or all sides), go ahead and blow the fire out and let them cool. Charred wood!

I ended up boiling the cubes at this point, it was something I wrestled with. On one hand, I didn’t want the tannic, strong oak flavors from the wood and since I am using them in primary they need to be sanitary. I have my doubts that my makeshift charring killed everything. On the other, I don’t want to remove those acrid sort of flavors I’m looking for from the char. I decided sanitation was more important, and boiling is how I typically sanitize anyways.

I ended up splitting 6 gallons of my Black Loch RIS, 3 gallons fermented on the oak cubes I charred and 3 gallons on nothing. I left both beers in primary for about 6 weeks, which is a little shorter than I usually advocate for aging on cubes, but just about where I usually bottle this specific beer.

Even before bottling there was a difference in the beers. The batch fermented on the charred oak cubes had a sharp roast flavor that had a relatively smooth finish. I really enjoyed it, but I didn’t want to come to any conclusions without having both beers bottle condition for a few weeks and be chilled. In my experience, pre-carbed beer isn’t a wonderful indicator of the final product.

I bottled both batches, let them sit for three weeks (not long enough, IMO), and set them in the fridge. A few days alter I opened both.

The Review: Toasted vs Charred Barrel

Color was identical, both were black and opaque with a dark tan head, a bit creamy. The aroma was also pretty identical, I had the beers served to me blind in a triangle test multiple times and couldn’t tell a difference. I was hoping for the char to come through a bit here, but I’d guess a lot of the aromas left in primary. Or it just didn’t change aroma, who knows.

I’d like to say there is a clear difference in the beers, but I’m honestly not sure. In five triangle tests, I reliably selected the odd beer out. However, I also let a lot of friends sample the beers and they couldn’t tell the difference. Note that it wasn’t a blind triangle test, they knew the beers were different, but they didn’t see it. It’s entirely possible I only selected correctly because I knew what I was looking for, and it’s also possible that I selected the odd beer correctly each time out of luck (really not that hard to do with a sample size of 5).

In my opinion, the beer fermented on the charred oak had a sharper characteristic in the roast, just like at bottling. There was definitely some wood character, a toasty quality that I’ve come to love from medium to medium-heavy oak American Oak. There wasn’t really an acrid characteristic like I was looking for, but I absolutely felt that the roast was a bit sharper and more complex than the ample amounts of roasted barley and chocolate malt I usually use typically deliver.

It occurred to me early on that I should test the char in another way, and so I also soaked some of the charred oak in vodka, alongside some medium toast oak cubes that hadn’t been charred. Sipping the liquors, the charred batch was darker and more defined, but I wouldn’t say sharper. Almost smoother honestly. The medium toast batch was a little sweet, oaky, and had hints of vanilla, characteristics that were far more restrained in the charred batch.

I really think the char contributed to the beer, and it’s something I’m going to dedicate more time and official tests to it in the future.

Conclusion

Toasting and Charring are two ways to get different characteristics our of your beer. Changing these attributes opens up the sort of contributions you can get from the wood, and understanding the role of different levels will help you find narrow down the wood you’d like to use for your beer. This post wasn’t really meant to be a comprehensive post on charring, and it isn’t by any means, just to introduce the differences between toasting and charring and starting down the path to exploring these concepts further.